Making Of

Behind The Block Prints

From the fabrics that fill Bapu Bazaar to the more modern takes at PDKF Store and Anokhi, block prints are synonymous with Jaipur. It would be impossible not to be inspired by them for my tablescapes. The first dinners I created on our apartment's terrace inevitably used block printed fabrics - it was a must. But I didn't expect to become so taken with the style that it would push me towards my first foray into design.

Gin spritzes under the parasols with glittering street lights on the horizon, the dinners we hosted on our pink terrace will forever hold a place in my heart. What a joy to be so far from home but find even more fun amongst friends old and new. I found myself drawing the bougainvillea of our terrace and the roses of the table centrepieces time and time again. It felt only right that they would form my first set of napkins.

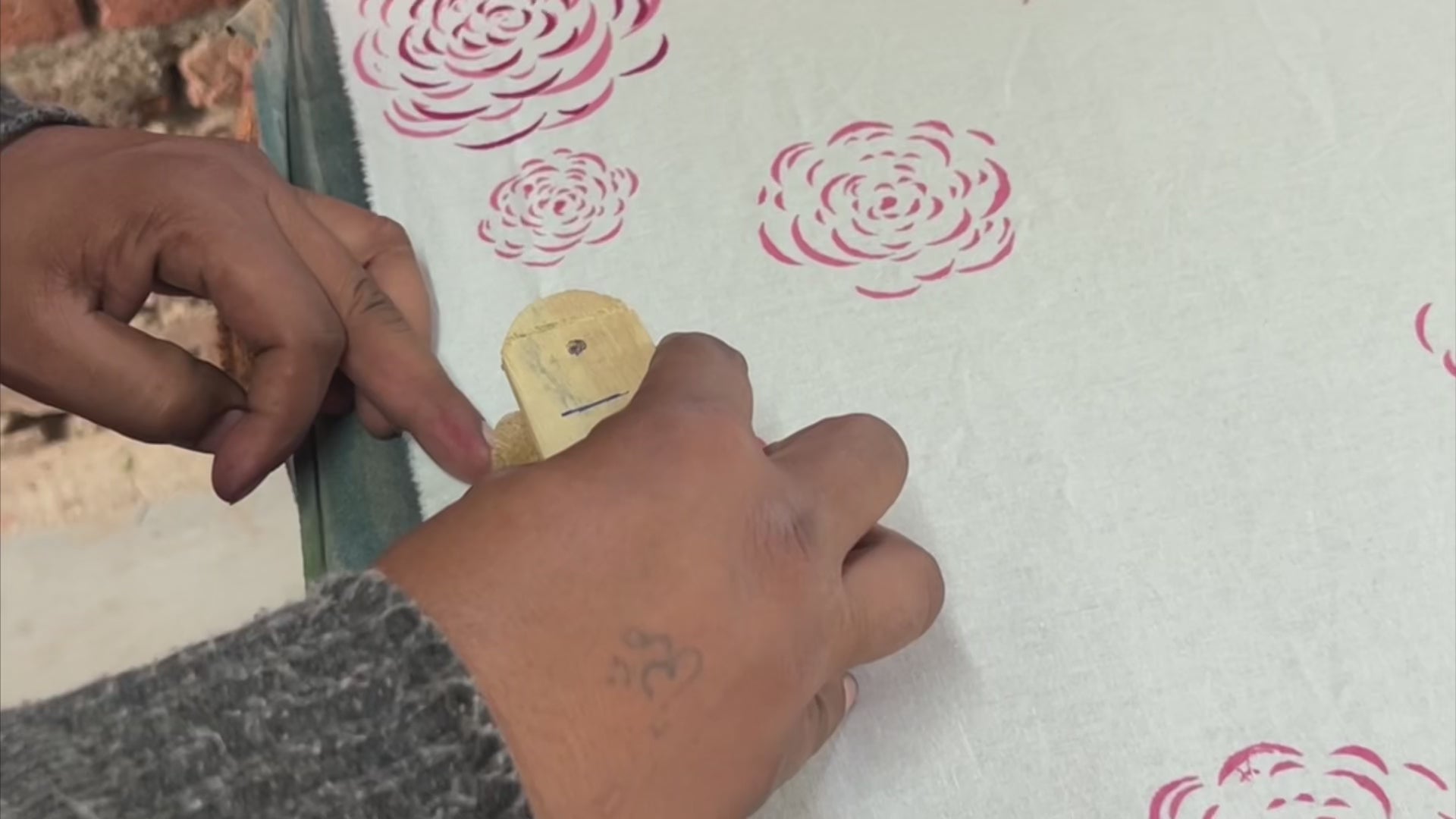

But forget the parties, creating these designs was the most fulfilling, stimulating and inspiring journey of my time in the city. Once I had drafted my designs in pencil, iterating over the point of a leaf of the curve of a petal, they were traced onto teak and chiseled by hand into wooden blocks.

"While printing designs onto fabric most likely originated in China about 4,500 years ago, it was on the Indian subcontinent where hand-blocked fabric reached its highest visual expression... Between outside influences and the diversity of the subcontinent’s own indigenous communities and tribes, India has yielded one of the most magnificent pattern vocabularies ever."

DEBORAH NEEDLEMAN, THE NEW YORK TIMES

My first visit to the printers was on one of those perfect Jaipur afternoons: the sun dipped so low that the air became a pink haze. Down a bougainvillea lined path I went; even from a distance I could hear the rhythmic thump, thump, thump of the artisans at work.

Inside, long tables covered with fabric, slowly, rhythmically being transformed: the chippas dip their blocks in shallow trays of ink, then stamp - quick, firm - and lift. Onwards they go... It is a mesmerising activity of talent at its most honed and dexterity at its most precise, not to mention an eye for detail. For example, for the two pinks in the roses of the tablecloth: the coral pink is stamped first and then the printer must place the second block, dipped in magenta, just so. Any misplacement will mean the petals overlap.

As I learnt quickly, the pressure on the wooden block is an art: too much and it will smudge, too little and it will fail. It took me a few samples to get the knack! But minor imperfections, which I've noticed as I check over each napkin, are the beauty of the craft. They signal a human hand and story involved rather than the dull accuracy and symmetry pumped out on repeat by a machine.

It was a privilege to learn from the talented purveyors of this craft. Dating back at least 300 years, this is a technique that has been handed down from generation to generation, parent to child. Inevitably, like so many ancient arts, it has been teetering on extinction due in part to the digital revolution and the new generation tempted to more lucrative work in the cities. That said, it is now thriving in Jaipur with designs exported globally.

"These designs are my ode to those cherished 5 months in Jaipur. If I've shared the marvel of this ancient craft with even one more person, my aim is complete. Preservation of these artisans' printing is paramount, imperfections and all."

Shop the look